Blog 18 - Wednesday, January 17th - To a Mouse

- Ashleigh Ogilvie-Lee

- Dec 14, 2025

- 5 min read

Mum comes to the door a bit hunched this morning, as if she is copying me. It’s Tuesday, and this is the day Ernest, her financial advisor, rings her, which he has done ever since Dad died 13 years ago. Ernest is one of Mum’s favourite people, and although she has never met him, she spins him, like all her favourite people, into a fairy-tale character. He is the woodcutter who saved Grandma from the wolf. When not saving grandmas, Ernest treads softly on Mother Earth in gratitude for her generosity; he builds his very own cottage, grows his own food, and walks around the South Island admiring Mother Earth’s infinite beauty.

He calls Mum Mrs McKegg, and Mum writes down every word he says in her loopy little writing, practised in those French school books with tiny squares. She goes to make a cup of tea while she waits for him to ring. By 8.10 he hasn’t rung, and I go to check I haven’t inadvertently unplugged the landline phone. Mum says I’m becoming a little worrywart.

At last the phone rings, and she comes to my room to tell me the air-conditioning men are bringing the air-conditioning unit back, but she’s not sure when. She checks my room for sloppiness and sees her lovely mohair blanket on the floor and picks it up, folding it, then pulls my computer charger out from the wall, saying this can cause fires. I think of Moo Hefner’s original girlfriend—the one he left me for, but not the current model—who was as stingy with her money as I was reckless. Moo Hefner used to say proudly, “Lizard turns every switch off at the wall at night.”

It’s 8.30 and Ernest still hasn’t rung, and we are not sure when the air-conditioning men are coming, so we mooch around in the kitchen, not wanting to begin our breakfast because of the likelihood of future interruptions. I read an article out loud from the Herald about a female sailor who groped three fellow sailors, and this is quite enough for Mum to jump up and go and have her shower. I put on a dress in case the air-conditioning men come while she is in the shower.

I am just spooning out the porridge when the door buzzer goes and it is the air-conditioning men. Mum comes into the kitchen pulling her white shirt over her head.

Half an hour later, with the air-conditioning unit successfully back in its rightful place, we are sitting at breakfast. I tell Mum my stomach hurts after I walk, and she says, “Why do you have to walk? It is the new mantra—one must walk all the time. But do we really have to?” I look at her in such fine fettle and wonder, do we?

“What are we going to do with all the bread now we are not allowed to feed it to the birds, who are now gluten-free?” Mum asks. I see her later sadly cutting up some very hard bread into chunks and throwing it down the waste disposal.

Charley comes to take me for a walk, and we have an omelette at Browns, where Mum had expressly told me not to go to, as they charge $9.50 for a slice of caramel slice. Charley tells me he has fallen in love with Onehunga, where he is now living, and his ex-wife, Heidi, says he has a flabby arse, that he’s the worst father in the world, and to go and get his girlfriend pregnant—and while he’s doing all this she is going to go to the IRD and pull the kids out of school.

As evening falls, Mum and I sit watching The Chase, but she is restless, as she always needs to be doing things. Watching her busily doing anything but chill makes me understand why my kids get so annoyed with me when I fluff around and jump up from the table just after I’ve sat down to get salt or water.

I read her an article in the Listener about a case in Remuera where a society eye doctor allegedly killed his wife. Mum says, “I am very snobby about these things—I just don’t read them. Why would I want to watch that wife of the prince being paraded naked through every village in a witch hunt? We used to be more discreet in the past. Now everyone breaks down and needs counselling. It absolutely leaves me cold. These things have happened since time immemorial. Now everyone has a story to tell, and it just becomes less and less interesting.”

She dips her finger in the boiling potato water to check I have salted it and tells me to give asparagus a chance, as not only are we being silently programmed to walk and not feed bread to the birds, but also to undercook our vegetables.

We watch Our Big Blue Backyard, and we see the katipo female spider catch a grasshopper, paralyse him, put him in her pantry, and nibble on him when she feels like a snack. Mum used to call Charley Grasshopper Green, and I think of him sitting sadly in Heidi’s pantry.

We see godwits fly the longest journey in the world from Alaska to New Zealand non-stop to feed their young; grandmother whales guide their pods through treacherous tides to feed their young; and tuataras, around for 200 million years, wait languorously all winter to gobble up the newly hatched spring chicks. Mum squeezes my hand and whispers, “It makes you believe in God.” Then the ads come on, and we see humans not even getting out of their car to feed their young some sort of unidentifiable food that comes in a brown paper bag with McDonald’s on it. Thor Heyerdahl (Kon-Tiki) says human progress is synonymous with distance from nature, and we have progressed so far our food and our intelligence are artificial, and now our dogs are watching television.

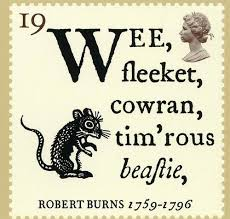

I tell Mum some good news: Gus’s mouse, Owen, is thriving. Mum jumps up to get her book on Robbie Burns and reads me “To a Mouse.”

Wee sleeket, cow’rin, tim’rous beastie,

Oh, what panic’s in thy breastie!

She says, “What a marvellous man he must have been to see a mouse like that,” and I think Gus is like Robbie Burns, even if he hasn’t fixed my curtain rail.

A video comes up on Facebook of Heidi’s mother encouraging her cat to catch a little mouse whose breastie is quivering as he waits for death under the wardrobe.

Thy poor earth-born companion,

An’ fellow-mortal!

❤️