Blog 13 - Friday January 12th - Un Enfant Unique

- Ashleigh Ogilvie-Lee

- Nov 2, 2025

- 6 min read

Last night I noticed Mum’s voice getting a bit hoarse, but when she comes into my room at 8:10 she seems cheery. I can tell immediately how she is. Her face can be quite drawn. She has had two links removed from her watch and it is still loose. She’s wearing her little house coat with flowers — it’s creamy yellow, which would wash anyone’s face out; it’s a sort of old toenail colour.

“I will wash the strawberries and raspberries,” she announces. She has the paper tucked under her arm. She does not pick up my dejected tea bags or soggy crumbs of milk arrowroot biscuit which I carry into the kitchen.

I say, “What a grey day,” and Mum nods approvingly, as if acknowledgement of the weather is how polite people start the day.“Not grey — miserable,” she corrects me.

We talk about the floods that are doing what floods do — flooding.“Mum, if I were sitting in a flooded house in Gisborne right now, the last thing I would be able to do would be to sweep the water out from under my bed,” I say sadly.“But darling,” she says, “there are always those people who will help the vulnerable.”

She is intrigued by people saving a little boat club while so many homes have been lost. People constantly surprise and disappoint her. The animal world pleases her with its uncomplicated rules: born, eat, live, procreate, die.“It’s the same for all of us,” she says, “but humans make such a big to-do about it.”

I think of Macbeth: “Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage, and then is heard no more.”

I love that Mum is such a realist and not weeping all the time like I do. She will watch dispassionately as a great petrel holds a mother penguin under the water until it drowns, while I weep copious tears for a little feathered creature I never knew. When something charms her, she claps her hands in a small gesture of prayer.

She believes the world is better off with cornflakes and cannot believe people are queuing for Prince Harry’s book Spare.“One thing about a book,” she says, “is that it is around for a long time. You don’t have to beat down the door for it.”

She thinks that Camilla has caused much grief and that Charles can’t even change a tyre.“Now the Queen, on the other hand,” she says proudly, “likes to change a tyre. That’s why she goes to Balmoral — to change tyres.”

The two blades of the electric knife are in the dishwasher and I say, “Look, Mum, watch me put the knife away.” I have to stop her jumping in to put them away, as she does with translating our French book. I overlap the knives carefully in their original box and put the box at the bottom of the correct cupboard.“Good,” Mum congratulates me. “Now next time you won’t have to think, Where did I put the bread knife?”

I say, “Mum, can I make a suggestion?” and she nods encouragingly.“Can we move the little white cups that we use all the time in front of the big green ones?”“I consent,” she announces.

I give her a vitamin C sachet and we agree to meet for coffee at 11, with Mum warning me to take great care in the shower.“It will come with great force and be hot. Do you want a shower cap? It’s on the back of the door.”“I know, Mum!”

I laugh. She laughs. We laugh.

We have coffee at 11 a.m. I have a chocolate biscuit, but she opts for shortbread, saying, “Chocolate is to be taken seriously — it is to be eaten only at the end of the meal. We don’t take chocolate seriously enough.”

I feel guilty about having eaten the chocolate biscuit. My guilt makes me realise I have always seen Mum as the arbiter of what is good and what is not good for me. But she says, “You’re a big girl now. You can make decisions for yourself.”

Mum drives me to get my hair done again — my third outing in two weeks. We drive past the wooden church with the steeple and I do the old hand game: Here is the church, here is the steeple, open the door, and here are the people.

Mum says children still love this game and says I must show it to the grandchildren. But we have forsaken our steepled maraes and today we open the door, but where are the people?

Nina does my hair and says I must put lipstick on, but I want to look tragic.

I go to my house next door to the hair salon. Charley is eating a Subway salad, Gus is in green, and Bella rolls over to have her tummy scratched and nudges me when I stop. I thank Lynnie for looking after the house and she says, “Don’t thank me, thank the good Lord.”

Nanny comes to pick me up; she is wearing the dress she said she wouldn’t buy because she’s on a budget. She says she goes swimming in the nude at her mum's garden and has to hide from guests who pay $20 for the garden tour — not to see Nanny in the nude.

I am so comforted to get back home to Mum and we read our French book together. The mother, Elise, is wailing because her kids have left home and her boss at work is sick of her wailing.“You don’t really think they’re going to stay until they’re fifty?” she asks Elise. “One doesn’t have children for oneself. I don’t understand this tendency women have to possess their offspring.”

“I can relate to the boss,” Mum says.

She tells a story which, like most of her stories, I have heard many times but never tire of.“When I was a little girl, I used to go and stay on a farm with Auntie Ellie, who was married to Uncle Norman and lived in Halcombe. On my first visit I nearly missed my train station because my parents had told me to get off just past Paekok. You see, darling, I never knew I had passed Paekok because I didn’t know it was just the nickname for Paekakariki. New Zealanders always shorten things. When I tried to explain this to Auntie Ellie, she said, ‘You silly kid.’ Ash, you have to understand, kids weren’t adored then as they are today.”

I say, “You’re so funny, Mum,” and she says, “I don’t know about that, but it’s a fact.”

She gives a new twist to this familiar Auntie Ellie story, remembering a story from 85 years ago. I have never heard Mum laugh as much as when she tells me the story of Mrs Cornfoot, the cart, and the cake.

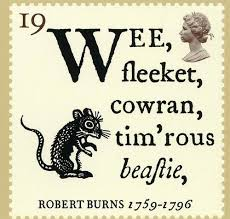

Although Auntie Ellie had no children of her own, Mum and her cousins Peter and Betty from Waitara went to stay on her farm every holiday. These holidays were the only time Mum was not an only child, Mum is, in fact, an intergenerational only child; an only child ,of an only child ,of an only child . This condition, she believes, defines her more than being French. “Oh, Ash,” Mum says, “Auntie Ellie was a noble woman, a model of patience and goodwill, and I was a proper example of a horrid, spoilt only child, used to always getting her own way.

One day we were all dressed up in our very best clothes because we were going to Mrs Cornfoot’s for afternoon tea. While we were waiting, I cajoled Peter into picking up the shafts of a farm cart and pulling Betty and me around. Of course, the cart tipped over into the muddy dam and we were such a mess we couldn’t go to Mrs Cornfoot’s. Auntie Ellie was confounded but maybe

somewhat relieved, as I think she was scared of Mrs Cornfoot, who would have sat there all afternoon alone with her specially baked cake — all because of me.”

I put the toast in.“You must put it twice,” Mum says. “The second time it will come up beautifully brown. You need your butter poised.”

I say, “We are out of Marmite.” “No! This is the first time in my life I am out of Marmite.” She is flummoxed. She goes to the cupboard and peers into the Marmite jar. “You’ll scratch enough for yourself. I’ll have peanut butter.”“Do you like peanut butter?” I ask.“Only on toast. I don’t go around eating spoonfuls of peanut butter.”

Mum says she doesn’t know why Moley and I bother with French. I say it’s like our Te Reo, but she doesn’t know why New Zealanders bother with this either.Mum says the actress playing Di in The Crown puts her head down too much — these sharp observations of Mum, like a hawk spotting a mouse.

🩷