Blog 9 - Monday 8 January – African Violets and Stoicism

- Ashleigh Ogilvie-Lee

- Oct 4, 2025

- 6 min read

Maryse is coming to visit at 1.

I walk into the kitchen chirpily, despite today signalling the end of tea and toast in bed.

"I am pleased with my writing," I say to Mum, to put a positive spin on the start of the day.

"Darling, your protests I have no need of, but it’s what brings you peace."

As we eat our porridge, we berate Prince Harry, as in a rare moment Mum casts her elegant mind over mindless matter, and were Spare to arrive in the house, it would be swept away like the poor spider on Nancy’s bouquet. I, on the other hand, won’t read Spare but will watch Married at First Sight—not religiously, but occasionally—so I can talk to Ashley, as she removes my errant facial hair, about the shameless behaviour of these modern Dickensian characters. There is a certain comfort in the kinship we find with these complete strangers who struggle publicly, as we do privately, to believe in ourselves—which is perhaps even harder than believing in God.

There could not be a greater antithesis to reality television than the stage which my mother floats across, imbuing life with a magic that is increasingly hard to reconcile with the brutality of the modern world. She can make you have feelings for a dish cloth.

“Dear little dish cloth,” she will say as she hangs it on the line, and it flaps shyly.

Mum’s apartment has a large formal room. She says she likes the feeling of space but says formal rooms, like the family silver, are gone with formality as she pours tea for her guests from the ceramic cat Moley gave her in the little nook off the kitchen. My grandmother’s abstract paintings take up most of the wall space, and there is a large bookcase which has travelled through life with us, with many of the books written by her old university friends like Carl Stead, James McNeish and Fleur Adcock. I like the books that Dad liked—Somerset Maugham and Graham Greene—and I wish I had read them before Dad died, so we could have talked about them together. But you can only relate to books that help you make sense of the life you are living at a certain time.

My favourite thing in the whole house is a piece of bone carved like a baby polar bear. I remember the little stuffed polar bear in a glass cage at Auckland Zoo. Its mother had drowned it rather than condemn it to a life in captivity.

I go for a walk to stop my bones from crumbling. As I leave, I call out,

“Mum, shall I lock the door?”

She pops her head around her bathroom door with her purple shower cap with frills and flowers that we share—and says,

“I don’t think I’m going to be unlucky enough to be attacked while you’re away. Don’t be too long.”

The sun is shining. I am so glad I didn’t die. I feel this huge responsibility to translate the millions of words I have written over my lifetime into something intelligible—like a Persian carpet of words—so it can be thrown to the ground and trampled on until my words too become dust.

I want to forgive my children for not fixing my window or moving a branch that has fallen across my front garden. I want so much to love and be loved by them, but think it might be easier if we didn’t live in the same town—as then I wouldn’t know what they didn’t do for me.

I walk across the crossing so slowly it looks like I am deliberately provoking stressed drivers. I remember when I used to spring across the crossing and perform that cultural habit of Kiwis, giving a shy wave to drivers as if to say thank you for not running me over.

Cyclists, runners and walkers whiz past like fluorescent blowflies, all dressed in tight Lycra t-shirts and pantyhose—now called leggings, but still just long panties.

I come home to Mum gently watering her African violets. She is bouche bée that a neighbour is mowing the lawns on a Sunday.

“That, darling, is just not considerate.”

I tell her about the attire of the skinny inhabitants of Remuera.

“Well,” she muses, “athletic gear allows them to move more freely, but it’s hardly as if they are going to lie down on the footpath and stick their legs in the air while shopping. These are people who don’t care if they pay $12 for two Afghans.”

She is more interested in her violets.

“Ash, my violets are a source of contentment and tribulation. I grew them from scratch. They all thrived and I’ve been trying to get rid of them ever since. I tell everyone how clever I am, and they all agree—but no one wants one. Only a friend of Moley’s has taken one. Overwater them and they die. I wake up at night. Did I overwater my violets?”

“I will introduce you to a wonderful book called Matthews on Gardening. But you are like me—full of enthusiasm, then you lose interest. But you can’t do that with plants or they will die.”

Maryse arrives swinging a basket for lunch like Red Riding Hood, and her health is alarming.

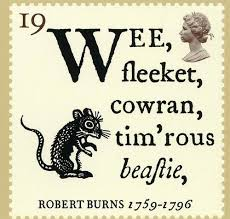

Maryse is now doing Stoicism 101, and is reading a book by the father of Stoicism, Marcus Aurelius. She is going to make a constant effort to abide by the four principles of courage, justice, temperance and wisdom. Her husband Boydie was born a Stoic, and when Maryse broke her leg, he made her climb backwards up the stairs—which is in sharp contrast to Mum’s method of tending me like an African violet.

My old boyfriend Leo, after 60 years of psychiatry, simplifies the lofty goals of Marcus Aurelius for the common man into agreements, not principles: Don’t make assumptions. Always do your best. Don’t take things personally. Be impeccable with your word.

At times when I am feeling lonely I try to relight a flame in this old romance but suspect I have well and truly doused it.

I try to meditate, but find the daily tribulations of interactions with utility suppliers, Auckland Transport, Baycorp, and people on different bases of the Vedic journey hamper my search for eternal bliss.

Maryse says she can’t believe how busy she is at Pakiri—making tea and pesto and mowing the lawn—so she can show off a circular route around the house.

She sees me writing and says,

“I remember when you were scribbling away in Melbourne and Neville (our hairdresser) and I looked at each other warily, wondering what you were saying about us. But we know we will never see a word you write.” (These blogs being my unveiling.)

I wonder if there is a condition for people who feel compelled to write all the time.

She tells me to put eyebrow mousse in my hair.

Sneezing and coughing hurt, but Maryse makes me laugh. She says while she is studying Stoicism, I must study budgeting.

She leaves to begin her first step of Stoicism, which is to clean out her house and then swim in cold water.

After she has left, Mum and I turn on the news and watch a mullet competition, a boy with cancer who wants to be a YouTuber, and Elvis impersonators—88 years on.

Mum sighs,

“I can’t believe people can be bothered.”

We watch The Two Popes, which is very fitting with the recent death of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, who is the last pope to be buried by his successor in 800 years. Pope Francis, who succeeded him, had never wanted to be pope, which is why he is so popular—as Plato said, the most important qualification in a leader is not to want to be one. The new pope tells the retiring pope to stop eating alone, as Jesus broke bread with his friends. They watch the final of the Football World Cup together and Germany wins, but even though the old pope is German, one is left with the feeling that he would still prefer playing the piano, eating alone and watching fictional dog shows.

A little bowl of cherries sits on the round table as the night filters through the blinds and wraps around us like a benevolent ghost.

Comments